Resident Magazine November 2016. Read book reviews by Frederic Colier

Resident Magazine November 2016. Read book reviews by Frederic Colier

online. Feature article is about Michael Shannon. Only in the Resident Magazine.

Resident Magazine November 2016. Read book reviews by Frederic Colier

Resident Magazine November 2016. Read book reviews by Frederic Colier

online. Feature article is about Michael Shannon. Only in the Resident Magazine.

“Heads,” by Jesse Jarnow

“Heads,” by Jesse Jarnow

(Da Capo Press, pp 468, $27.99)

If you are a fan of books dealing with the history of salt, timber or something more exotic like sex, you will delight in “Heads,” a book about psychedelics. Though the term has now gained multiple definitions, notably in relation to music and culture, the psychedelics refer to here belong to drugs, yes narcotics. A well-time book, given the massive popular wave to legalize Marijuana. However, you will find no bell chiming in favor of psych drugs.

In this well-documented spiraling history of how these drugs transformed our present culture, Jesse Jarnow offers a fresh outlook. While we can talk about peyote and other forms of LSD derivatives, it is impossible to understand the meaning of Psychedelic without going back to the 60’s, starting first as a counter-culture on the eve of the Vietnam War and the Civil Right Movements. Thinking Huxley having a bad trip in “Doors of Perception,” or Leary’s promoting drugs in Harvard, via Richard Alpert, aka Ram Dass, experiencing a spiritual awakening, would confine the movement to known anecdotes.

Jesse Jarnow has dug deep into the roots of Psychedelia. For a generation, which perceived itself as living in a repressive society, music became the catalyst of a cultural revolution, the bedfellow able to unleash repressed psychological emotions. If Grateful Dead means anything to you, I will set you on course, as you may wonder what “New Age practices, hacktivism, yoga, natural childbirth, Burning Man, Central Park graffiti, with artist like Bilrock and the late Keith Haring, and the internet, have in common. The answer may surprise you.

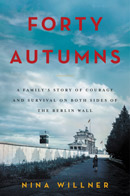

“Forty Autumns: a Family’s Story of Courage and Survival on Both Sides of the Berlin Wall,” by Nina Willner

“Forty Autumns: a Family’s Story of Courage and Survival on Both Sides of the Berlin Wall,” by Nina Willner

(William Morrow, pp 397, $27.99)

The title spells it all. “Forty Autumns,” is about survival on both sides of the Berlin Wall. If you know the history of the Cold War, you will quickly infer that we are talking about two different kinds of survival. East and West spell out different hardships. In the case of the East, we are dealing with communist repression on all fronts in a Big-Brother-like society, restriction of liberties, listening, spying, suspecting, ideological enforcement, in brief, a constant climate of distrust and cultivated fear. For the West, the survival is more nuanced. It comes from isolation, fragmented family, unfulfilled desires, which, perhaps, indirectly, is the consequence of the severed ties created by the Berlin Wall.

In this historical memoir, Nina Willner tells us the story of her family, the escape of her mother, Hannah, into the West, and her struggle to survive away from her family. A family she would only be reunited to 40 years later, after the fall of the Wall. “Forty Autumns,” emphasizes the metaphor that sometime politics and ideologies act as crushing silent forces standing in the way of families, and their reconciliation. What makes the book stand out from memoirs on the same topic comes from the author’s real life situation. Nina Willner worked for the American Intelligence and got to be stationed in Berlin, during the cold war, just a few miles away from her Eastern family . . . and got to lead missions into the Eastern block. No matter what, human spirit always prevails.

“Where Memory Leads” by Saul Friedländer.

“Where Memory Leads” by Saul Friedländer.

(Other Press, pp 284, $24.95)

If you remember the Pulitzer Prize winning book, “The Years of Extermination,” you will know at once that this review refers to Saul Friedländer. If you also know that he spent sixteen years writing his magnum opus, you could claim that he spent 80 years writing his new memoir “Where Memories Leads.” It is riveting account, the coda marking a life intertwined with the Holocaust, a project already initiated with his first memoir “When Memory Comes,” published more then thirty years ago (a book re-released at same time). Besides from the heart-wrenching topic depicting the trauma of a childhood spent during the Third Reich, watching his parents being deported, the memoirs have a different tone. The former deals with a man struggling with comprehension and uncertain answers about his life, at the peak of it, while the second has the feel of a man looking at his journey, with the mindset that he has reached the sunset of his life. The questions have been fulfilled, unless he is now reluctant to open new paths. With resignation comes insight.

Friedländer’s life has been defined by his “monumental” contribution to Holocaust Studies. The book spans his whole life, from his birth at the worse possible time, the beginning of WWII, to present day, fitting perhaps the cliché that most Jews encountered after the war: finding a home, moving from country to country, if not continent to continent. The book clearly stipulates that Friedländer found a home in the intellectual journey of his own childhood and destroyed Jewish heritage, by building a defense and knowledge that could not be taken away from him. It ultimately cemented his strong Jewish identity. This makes for a different stance, more confident, accepting, resigned, engaged and engaging.

“The Natural Way of Things,” by Charlotte Wood

“The Natural Way of Things,” by Charlotte Wood

(Europa Editions, pp 233, $17.00)

Though not her first novel, “The Natural Way of Things” is Charlotte Wood’s first print in the States. Better late than never, and it is wholly deserved. It is an intriguing book to come out at the time of perhaps the strangest presidential campaign ever, where one of the candidates is plagued with accusation of sexism and sexual misconduct. And this makes it hard to avoid the metaphorical subtext of Wood’s novel, reminiscent of Atwood’s “Handmaid’s Tale,” since we are dealing with women and sexuality in a repressive and controlling corporate-like society. Though I do not believe that women have anything to do to prove their competence and rights in this world, the protagonists of Wood’s novel are women deprived of rights and live a Kafkaesque nightmare.

Yolanda, the heroine of this dystopian novel, wakes up one morning in the middle of Australian desert, dressed in rags, and not remembering how she ended locked up into a ward. She however quickly learns that along with her roommate, Verla, that they are now captives of a strange repressive system, exercising a systematic corporate control on their every move. The reason that binds them is the scarlet letter they wore, a past sexual scandal. Very quickly, rather than accepting their fate in a place where women are drudged and subjugated to fear, they escape into the wild. More than a story where the hunted becomes the hunter, they must develop the skills of survival and trust. In a world fraught with violence, the women of “The Natural Way of Things” must find resilience and seek redemption.